Flash boys want flash markets. Exchanges invest to make their matching engines clock at ever higher speeds. High-frequency traders claim they can provide more liquidity as a result. Investors – the low-frequency traders in the market – benefit from a lower bid-ask spread. Is this true? Is it even true that high-frequency traders themselves benefit from faster markets?

In a new study co-authored with Marius Zoican, I claim the answer to both questions could in fact be: no, no one benefits. And if none of the market participants benefit, then it cannot be good for the exchange either. A puzzle.

The study proposes a model of trading with speed at the heart of it. What drives the ‘surprising’ findings is that only high-frequency traders have the speed to benefit from a faster, sub-millisecond exchange. As market makers, high-frequency traders can update their price quotes faster on news. But, equally important, as speculators they can hit the quotes of rivals faster on news. The market becomes more of a speed game between high-frequency market makers and high-frequency ‘bandits.’

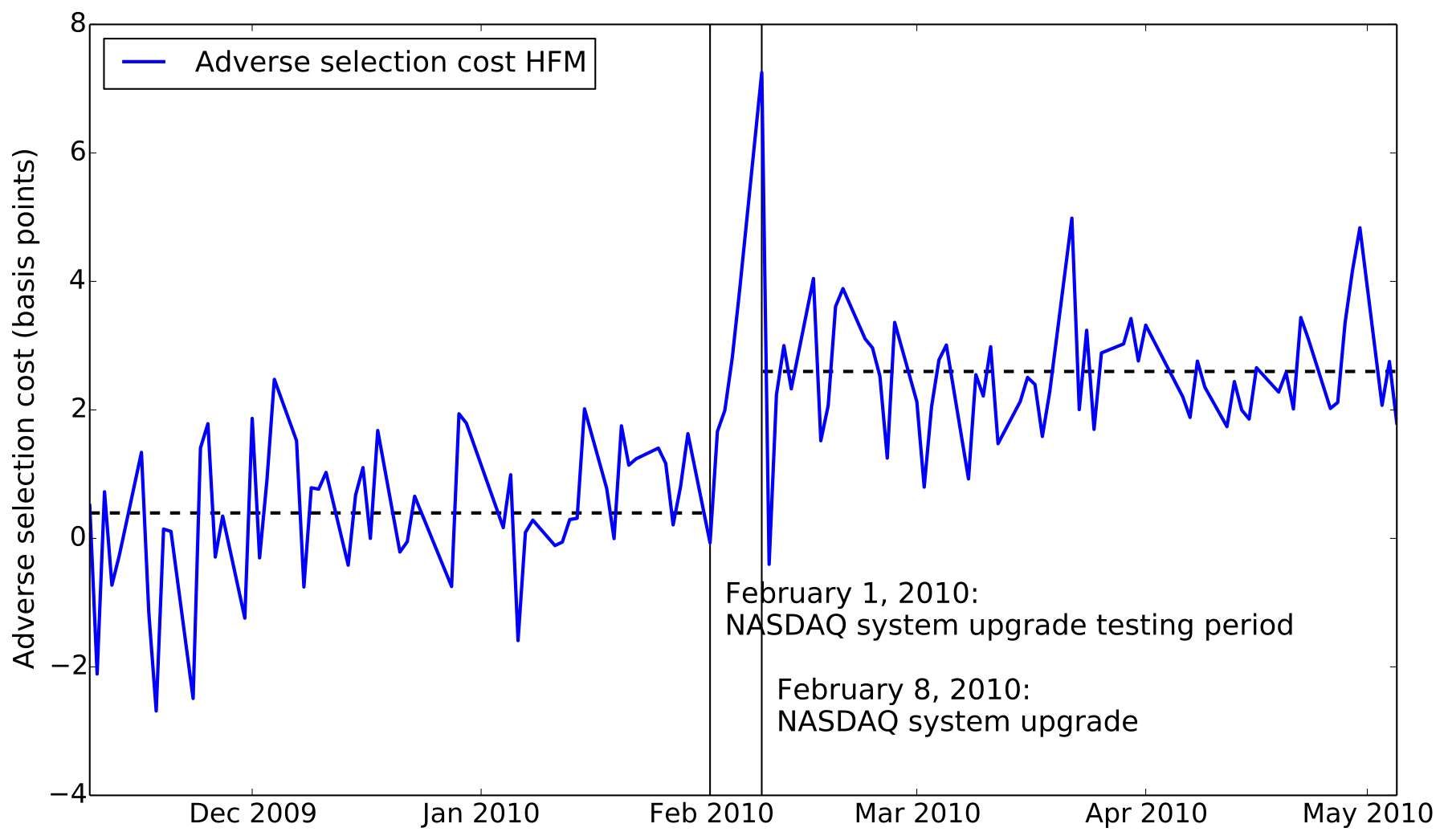

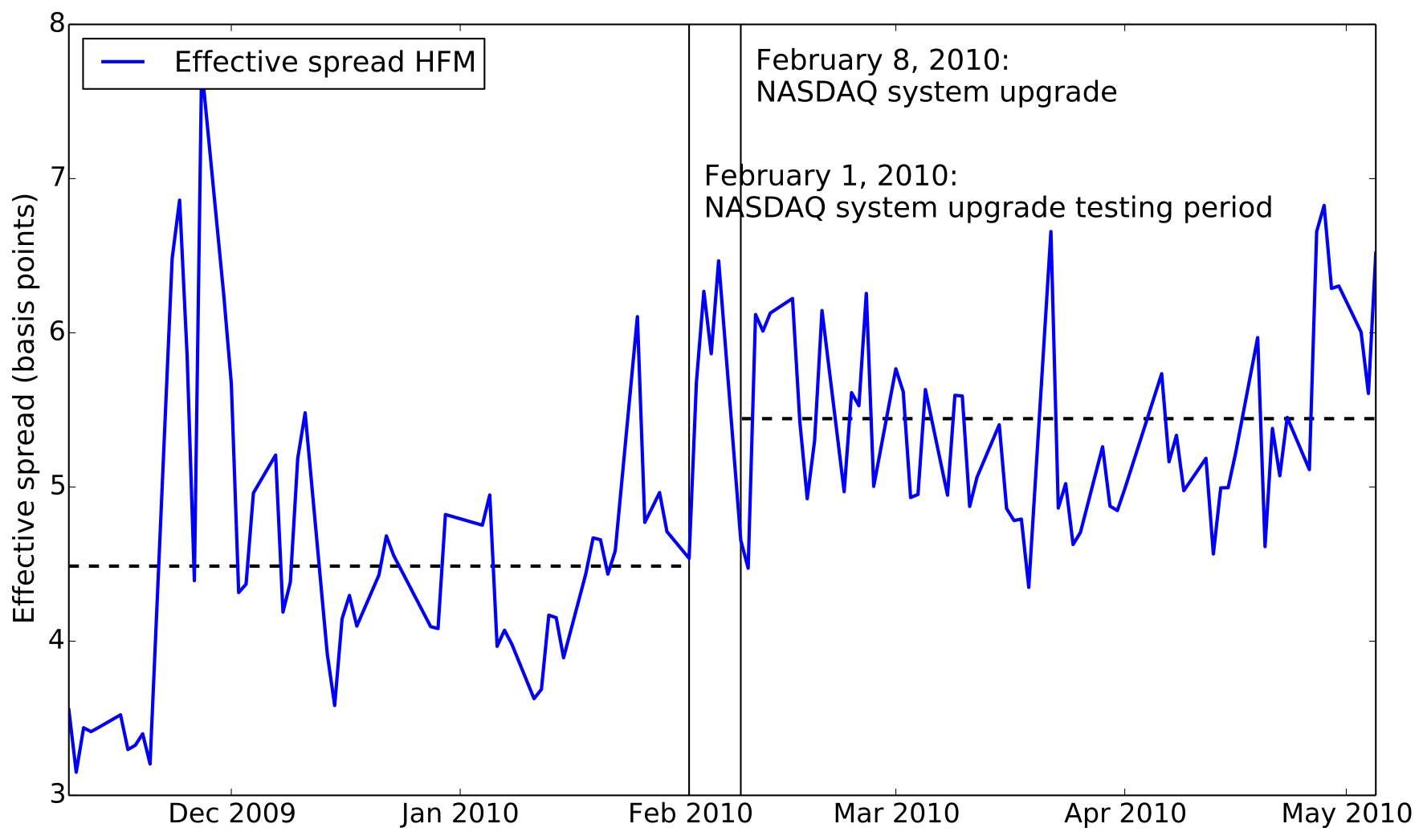

When high-frequency market makers meet high-frequency bandits, they lose in these trades. As a faster exchange implies more of such meetings, they have to raise the bid-ask spread to recover the increased adverse-selection cost. Investors pay a higher spread as a result.

These theoretical predictions are tested based on a sample of Nordic stocks surrounding a 2010 Nasdaq-OMX speed upgrade. We were able to identify five high-frequency traders in the sample. The main empirical result is that the adverse-selection cost indeed rises for price quotes of these firms (after inclusion of standard control variables). And, perhaps more important, the effective spread they charged increased along with it. These findings are illustrated by the following two graphs.

Covered by Bloomberg. Commented on by Brad Katsuyama, the main character in “Flash Boys,” by Michael Lewis.

You find the paper here.