This image reminds me of crossing the German border in my childhood days. Passport inspections slowed all of us down, resulting in traffic jams. This is the price we all paid for control by national authorities. Small for each household, but sizable if multiplied by the sheer amount of cross-border traffic.

A modern version of this type of friction is fragmented clearing. Financial institutions hedge local risks by trading derivatives with foreign investors. They cross borders and local risks get diversified globally.

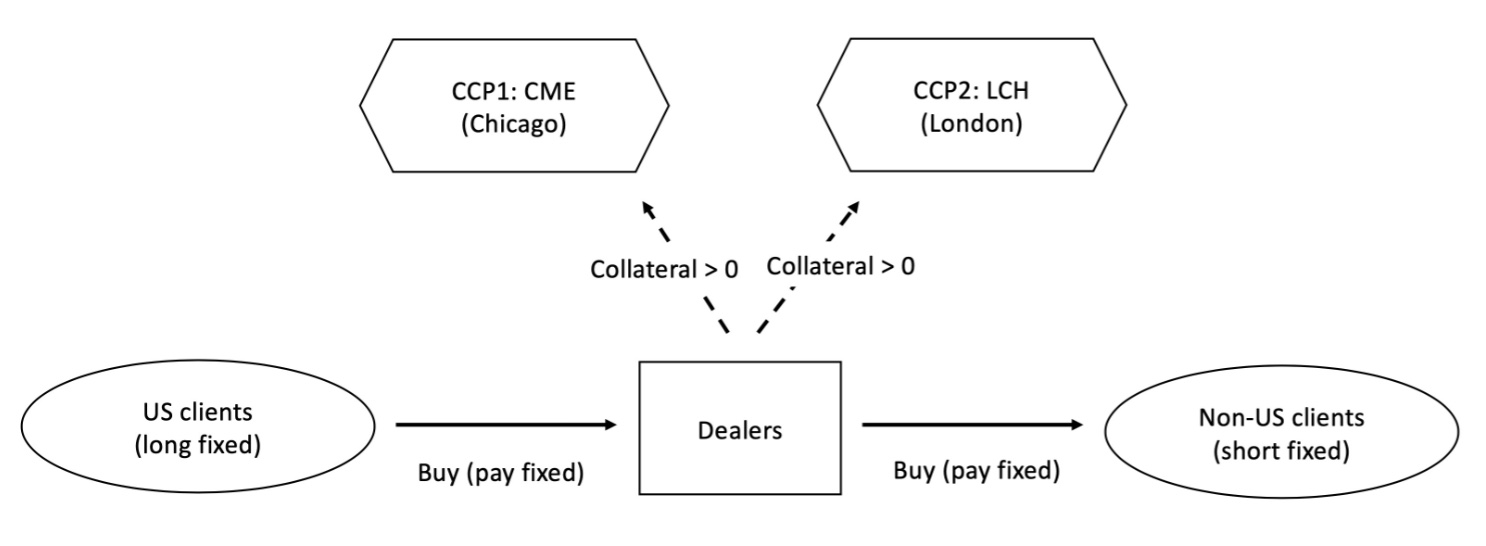

Local authorities want financial stability. They therefore mandate (standard) derivatives to be cleared through central clearing parties (CCPs). More specifically, buyers and sellers of derivatives need to post collateral (“money”) commensurate with the daily value at risk in their positions. This ensures that both sides to derivative trades are able to honor their commitments. The system becomes reliable and stable.

So far, so good.

The trouble, however, starts when local authorities exercise control locally. If local institutions need to clear their trades locally, then global dealers will still facilitate cross-border hedges, but at a cost to locals. The reason is that local buyers buy from global dealers who, in turn, buy abroad from foreign sellers. The cross-border hedge is still in place.

So, why is there a cost to locals?

Well, global dealers have a position in derivatives locally, but not globally. In the example thus far, global dealers are short the derivative in the local CCP and long the same derivative in the foreign CCP. They need to post collateral in both the local and the foreign CCP, but do not constitute risk to the global financial system. In other words, in the hypothetical case of a global CCP, they would not have to post collateral since their net position is zero. Fragmented clearing is costly.

Ah, but still, why is this costly to local institutions?

The capital that global dealers need to fund the collateral is costly to them. They will pass these costs on to their clients by selling to local buyers at a strictly higher price than the price they pay when buying from foreign sellers. This price wedge is there even in the case of perfect competition in the global dealer market. It is referred to as the CCP basis. It is small for each unit of risk that crosses the border, but becomes sizable if multiplied by the sheer amount of cross-border traffic.

In a recent paper with Benos, Huang, and Vasios, we thoroughly study the case of US financial institutions hedging US interest rate risk with the rest of the world. These institutions hedge this risk locally by buying interest-rate swaps from global dealers. These trades clear in Chicago at the CME. These global dealers, in turn, buy interest-rate swaps from the rest of the world and clear in London at LCH.

In the paper we offer a formal economic model and utilize unique clearing data to assess the cost of such fragmented clearing. We find that the CCP basis is in the order of basis points. But, small as it sounds, when multiplied with cross-border volume, the fragmented-clearing friction costs LCH sellers $80 million daily in our sample period (2014-2016). (Net of LCH buying, the cost is $3 million daily.)

I believe clearing might further fragment in the aftermath of Brexit. Negotiations are currently taking place and fragmented-clearing across the English Channel could be the outcome. Given that dealer funding costs today are at similar levels as in 2014-2016 and assuming the friction scales with GDP, then such fragmentation could cost London sellers €50 million daily. (Net of buying, it would be €2 million daily.)

As a European citizen I can now zip onto the Autobahn with 100+ kilometers per hour, but my pension fund might soon pay for crossing the border with the UK to diversify risk.

P.S.: Please find the paper with Evangelos Benos (University of Nottingham), Wenqian Huang (BIS), and Michalis Vasios here: The Cost of Clearing Fragmentation.

P.S.2: Covered by Bloomberg.