Regulators aim for transparency. In securities markets, they mandate publication of ever more data in the interest of investors.

But, who do they target in their zealous quest with ever larger heaps of data? Let us take the consolidated tape (CT) as an example. Sell-side banks or electronic market makers do not need a CT. These market participants acquire costly direct feeds from the various exchanges. A CT is too slow for them to feed into their smart routing algorithms.

So, it must be buy-side investors and retail traders who benefit from a CT. And I can see how. A CT allows them to judge the execution quality of their orders. Comparing the price they got to prices of surrounding trades will give them a sense for how good their execution was. If they consistently pay higher prices on their buy orders, or receive lower prices on their sell orders, then they should reconsider their routing. Or, start a conversation with whoever executes the orders on their behalf.

To me, this is the largest value a CT can create for investors. To unlock this value, however, investors should be able to process a CT with ease. It is here where I see some challenges, in particular when datasets contain huge amounts of records, and when each record contains numerous data fields. The point is that large datasets are hard to process for many investors and, in particular, for retail investors.

I therefore urge regulators to be aware of these considerations in their hunt for more data. The marginal cost of producing public data tends to increase with each data point. The marginal benefit (to investors) tends to decrease with every data point. Infinity is unlikely to be the optimal size of datasets…

The second point I like to make is that academics can be of value in this respect. They have developed methods to turn large heaps of data into useful information. One good example is how to analyze data to answer a very simple question: If a security is trading on multiple venues, then which venue should investors use as a benchmark to judge the quality of their execution? In other words, which venue generates the most informative price series? Joel Hasbrouck of NYU developed an approach to literally decompose information across venues.1 And, importantly, the approach only requires ordinary linear regression (OLS), which is available in any statistical software package. It runs even for extremely large datasets.

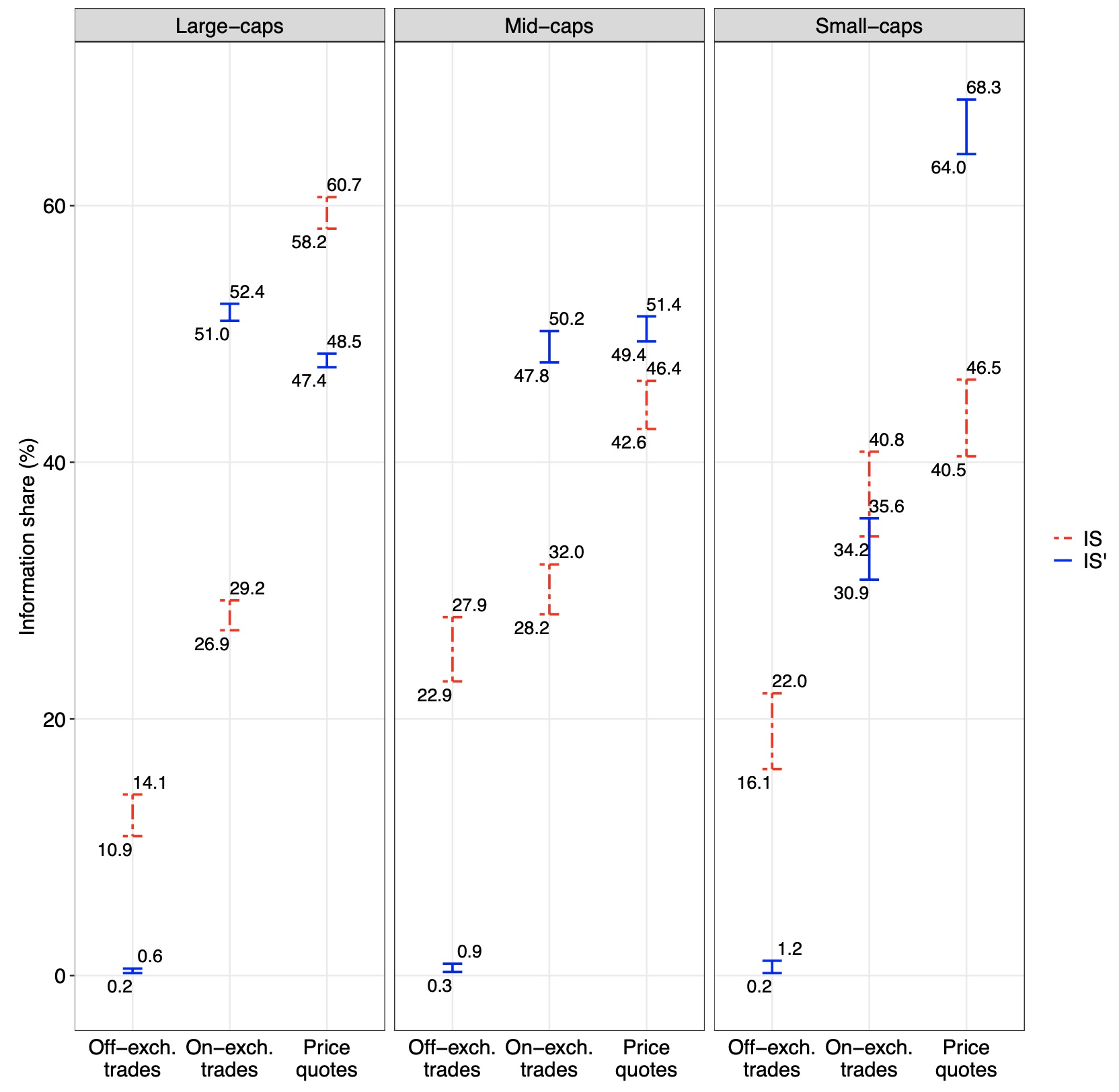

In a recent paper, Björn Hagströmer and I refined this approach to deal with transaction prices.2 (Our approach avoids forward-filling of such prices which can cause bias, but this is not for this blog post.) We apply it to trading in LSE stocks with an interest to learn the information shares (IS) of the following types of prices:

Please find the signature plot of the paper below, for your convenience. The unbiased information shares are denoted by IS'.

These results suggest that on-exhange trade and quote series, collectively, contain almost all information. For example, the result for large-cap stocks in the left panel shows that off-exchange trades contribute only between 0.2% and 0.6% to information (see blue “I”). The remaining 99.4% to 99.8% is generated by on-exhange prices. Quotes and trades each contribute about half of it. Similar findings hold for mid- and small-cap stocks. The only difference is that, for small-caps, the relative contribution of quotes is about two-thirds.

To wrap up, here are my thoughts. Datasets tend to get huge. The toolbox to analyze these data is growing rapidly as well, with the arrival of, for example, AI and machine-learning. This all might be a curse, rather than a blessing for investors. I believe they are helped by relatively simple tools that run on large datasets to extract informative and manageable datasets. Maybe investors are best off with datasets that download instantly and open in Excel?